Black History Trivia

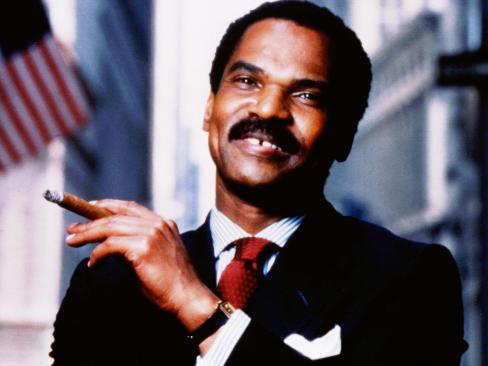

- This businessman was the first African American to build a one billion dollar company.

Reginald F. Lewis was born December 7, 1942 in Baltimore, Md. He excelled in academics and sports in high school. Entering Virginia State University in 1961 on an athletic scholarship, Lewis majored in economics. In his final year, Harvard Law School began introducing Black students to legal studies via a summer program. Lewis was selected for the program, and was invited by Harvard to attend its prestigious law school.

Reginald F. Lewis was born December 7, 1942 in Baltimore, Md. He excelled in academics and sports in high school. Entering Virginia State University in 1961 on an athletic scholarship, Lewis majored in economics. In his final year, Harvard Law School began introducing Black students to legal studies via a summer program. Lewis was selected for the program, and was invited by Harvard to attend its prestigious law school.

With a focus on securities law, Lewis established the first African-American law firm on Wall Street, helping many minority businesses obtain much-needed startup capital. In 1983, he created the TLC Group, a venture capital firm known for corporate takeovers of struggling companies and then turning them around. Lewis’ biggest coup came on August 9, 1987 when he purchased the international division of Beatrice Foods. Renaming it TLC Beatrice International, Lewis rapidly turned around the company as its chairman and CEO. In 1992, the company earned over $1.6 billion annually.

In 1993, Lewis died at the age of 50 after a long bout with brain cancer. His wife, attorney Loida Nicolas-Lewis, took over TLC Beatrice and ran it until 2000. She still serves as chairwoman and CEO of Beatrice, LLC a family-owned investment firm.

http://www.lewismuseum.org/about/reginald-lewis

- Who was the first African American to earn an international pilot's license.

Emory Conrad Malick (1881 – 1958) grew up in central Pennsylvania. As a young man, Malick built and flew gliders. In 1911, Mr. Malick became the first aviator to fly over central Pennsylvania, flying his homemade "aeroplane" over both Northumberland and Snyder Counties.

Emory Conrad Malick (1881 – 1958) grew up in central Pennsylvania. As a young man, Malick built and flew gliders. In 1911, Mr. Malick became the first aviator to fly over central Pennsylvania, flying his homemade "aeroplane" over both Northumberland and Snyder Counties.

Malick was the first licensed Black aviator, earning his International Pilot’s License (Federation Aeronautique Internationale, or F.A.I., license), #105, on March 20, 1912. After earning his pilot’s license Malick obtained, assembled, and improved upon a Curtiss “pusher” biplane that in 1914 he flew over Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania.

In March 1928 at a Camden, New Jersey airshow, Malick took two passengers for a quick hop in his Waco three seater. They were barely aloft when the engine died. Malick banked to the left to avoid spectators; unfortunately, the wind caught the aircraft, and the Waco crashed. “The entire plane seemed to crumple as if it had been smitten by the fist of a giant,” reported the Sunbury (Pennsylvania) Daily Item. The two passengers were injured. Later that year, Malick crashed again the cause isn’t known this time injuring himself and killing his passenger. He never flew again.

Although he stopped flying after two crashes, one injuring himself and killing his passenger, Malick remained interested in aviation. In December 1958, when he was 77 years old, Malick died after slipping and falling on an icy sidewalk in Philadelphia. With no identification on him, his body was unclaimed in the morgue for more than a month, until his identity could be established.

http://emoryconradmalick.com/biography.html

- This mathematician’s groundbreaking work in satellite geodesy helped lay the foundation for the development of GPS technology.

Dr. Gladys Mae West (1930– 2026) was a mathematician whose precise calculations of the Earth’s shape played a critical role in the development of what we now know as the Global Positioning System (GPS).

Dr. Gladys Mae West (1930– 2026) was a mathematician whose precise calculations of the Earth’s shape played a critical role in the development of what we now know as the Global Positioning System (GPS).

Born in rural Sutherland, Virginia, West grew up in a farming family and excelled academically. She earned a degree in mathematics from Virginia State College (now Virginia State University) and later a master’s degree in mathematics. In 1956, she began working at the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia — becoming only the second Black woman hired there.

West was part of a team that used complex mathematical modeling and satellite data to determine the exact shape of the Earth (a geoid). Her detailed programming and data processing were essential to the accuracy of satellite positioning systems. Without this foundational work, GPS as we know it today would not function with the precision we rely on for navigation, smartphones, mapping, aviation, and countless other applications.

For decades, her contributions were largely unrecognized. In 2018, she was inducted into the U.S. Air Force Hall of Fame, and her story has since inspired a new generation of women and students of color in STEM.

Dr. Gladys West’s work reminds us that behind modern technology are brilliant minds whose impact reaches the entire world.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gladys-West

- In 1992 she became the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Carol Moseley Braun (1947 - ) was born in Chicago, Illinois, on August 16, 1947. The oldest of the four Moseley children in a middle-class family, Carol graduated from Parker High School in Chicago and earned a BA in political science from the University of Illinois in 1969.

Carol Moseley Braun (1947 - ) was born in Chicago, Illinois, on August 16, 1947. The oldest of the four Moseley children in a middle-class family, Carol graduated from Parker High School in Chicago and earned a BA in political science from the University of Illinois in 1969.

In 1972 Carol Moseley graduated from the University of Chicago School of Law. She married Michael Braun in 1973 (divorced 1986) and worked as an assistant U.S. attorney. In 1978 she won election to the Illinois state house of representatives, a position she held for a decade.

After an unsuccessful bid for Illinois lieutenant governor in 1986, she was elected the Cook County, Illinois, recorder of deeds in 1988, becoming the first African American to hold an executive position in Cook County. In 1992, displeased with U.S. Senator Alan Dixon’s support of U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, she ran against Dixon in the 1992 Democratic primary. She won an upset victory over Dixon on her way to capturing a seat in the Senate.

In the Senate, Moseley-Braun became the first woman to serve on the powerful Finance Committee when a top-ranking Democrat, Thomas Andrew Daschle of South Dakota, gave up his seat to create a spot for her. Also, Moseley-Braun and Senator Dianne Feinstein of California became just the second and third women ever to serve on the prestigious Senate Judiciary Committee.

In 1998 Moseley Braun lost her seat to her Republican challenger, Peter Fitzgerald. From 1999 to 2001 she served as U.S. ambassador to New Zealand. She unsuccessfully sought the Democratic Party presidential nomination in 2004. Moseley Braun subsequently founded (2005) an organic food company. In 2010 she announced that she would run for mayor of Chicago, but she finished fourth, winning just 9 percent of the vote in the February 2011 election.

https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/honorable-carol-moseley-braun

- Who was the first black woman to win a tennis Grand Slam tournament?

Althea Neale Gibson (1927 - 2003) was the first Black player to win the French (1956), Wimbledon (1957–58), and U.S. Open (1957–58) singles championships. She was born on August 25, 1927, in Silver, South Carolina. At a young age, Gibson moved with her family to Harlem in New York City. After winning several tournaments hosted by the local recreation department, Gibson was introduced to the Harlem River Tennis Courts in 1941. In 1942 she won her first tournament, which was sponsored by the American Tennis Association (ATA), an organization founded by African American players. In 1947 she captured the ATA’s women’s singles championship, which she would hold for 10 consecutive years.

Althea Neale Gibson (1927 - 2003) was the first Black player to win the French (1956), Wimbledon (1957–58), and U.S. Open (1957–58) singles championships. She was born on August 25, 1927, in Silver, South Carolina. At a young age, Gibson moved with her family to Harlem in New York City. After winning several tournaments hosted by the local recreation department, Gibson was introduced to the Harlem River Tennis Courts in 1941. In 1942 she won her first tournament, which was sponsored by the American Tennis Association (ATA), an organization founded by African American players. In 1947 she captured the ATA’s women’s singles championship, which she would hold for 10 consecutive years.

Gibson's success at those ATA tournaments paved the way for her to attend Florida A&M University on a sports scholarship. She continued to play in tournaments around the country and in 1950 became the first Black tennis player to enter the national grass-court championship tournament at Forest Hills in Queens, New York. The next year she entered the Wimbledon tournament, again as the first Black player ever invited.

Until 1956 Gibson had only fair success in match tennis play, but that year she won a number of tournaments in Asia and Europe, including the French and Italian singles titles and the women’s doubles title at Wimbledon. In 1957–58 she won the Wimbledon women’s singles and doubles titles and took the U.S. women’s singles championship at Forest Hills. In 1957, Gibson was voted Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press, becoming the first African American to receive the honour.

Having worked her way to top rank in world amateur tennis, she turned professional following her 1958 Forest Hills win. However, there being few tournaments and prizes for women at that time, she took up professional golf in 1964 and was the first African-American member of the Ladies Professional Golf Association. Following her retirement, in 1971, Gibson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. On September 28, 2003, Gibson died of respiratory failure in East Orange, New Jersey.

https://www.tennisfame.com/hall-of-famers/inductees/althea-gibson

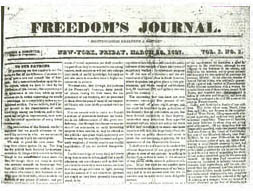

- What was the first black newspaper?

In 1827, Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwarm started the first African-American periodical, called Freedom's Journal. Freedom's Journal initiated the trend of African-American papers throughout the United States to fight for liberation and rights, demonstrate racial pride, and inform readers of events affecting the African-American community. Unfortunately, due to small readership, the paper ended its circulation in 1830. Another African American newspaper, the North Star, founded by Frederick Douglass, suffered the same fate as Freedom's Journal.

In 1827, Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwarm started the first African-American periodical, called Freedom's Journal. Freedom's Journal initiated the trend of African-American papers throughout the United States to fight for liberation and rights, demonstrate racial pride, and inform readers of events affecting the African-American community. Unfortunately, due to small readership, the paper ended its circulation in 1830. Another African American newspaper, the North Star, founded by Frederick Douglass, suffered the same fate as Freedom's Journal.

As African-Americans migrated from fields to urban centers, virtually every large city with a significant African-American population soon had African-American newspapers. Examples were the Chicago Defender, Detroit Tribune, the Pittsburgh Courier, and the (New York) Amsterdam News.

http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/newbios/nwsppr/freedom/freedom.html

- Lonnie Johnson, who was the first African American engineer to be inducted into Alabama’s Engineering Hall of Fame, invented what popular toy?

Lonnie was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1949. Going to school during segregation, Lonnie attended the all-black Williamson High School in Mobile where he was nicknamed “The Professor” by his friends. Lonnie earned a BS degree in mechanical engineering in 1973 and an MS degree in nuclear engineering in 1975 from Tuskegee University in Alabama.

Lonnie was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1949. Going to school during segregation, Lonnie attended the all-black Williamson High School in Mobile where he was nicknamed “The Professor” by his friends. Lonnie earned a BS degree in mechanical engineering in 1973 and an MS degree in nuclear engineering in 1975 from Tuskegee University in Alabama.

After graduate school he joined the US Air Force and served as acting chief of the Space Nuclear Power Safety Section. In 1979 he accepted a position at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where he earned multiple NASA awards for his spacecraft system designs. Despite this impressive resume, Lonnie is most famous for the results of inventive pursuits during his spare time.

In 1982 he was working at home on an environmentally-friendly heat pump that used water instead of Freon. The resulting powerful stream of water that blasted out when he pulled the nozzle’s lever inspired him to tinker with it as a potential toy. By 1989, he licensed his Super Soaker water gun to Larami Corporation, which was purchased by Hasbro six years later. By 2016 that sales figures for the super soaker had reached nearly $1 billion.

The proceeds from licensing his top-selling toy provided the capital to start Johnson Research & Development Co., Inc., in Atlanta, which later incubated two spin-off companies—Excellatron Solid State to produce rechargeable lithium ion batteries and Johnson Electro-Mechanical Systems that focuses on the Johnson Thermodynamic Energy Converter, or JTEC. Lonnie was inducted into Alabama’s Engineering Hall of Fame in 2011—the first African American engineer to be so honored.

http://www.biography.com/people/lonnie-g-johnson-17112946

- This civil rights activist, philanthropist and entrepreneur was one of the first American women to become a self-made millionaire.

Madam C. J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in Delta, LA in 1867. Her parents were sharecroppers on a plantation near the Mississippi River. She lost both her parents before she turned 8 years old and went to work in the cotton fields to survive. At 14 she married Moses McWilliams and had a child, Lelia, in 1885. Moses McWilliams died in 1887 and in 1894 she married John Davis. That marriage ended in 1903 and Sarah moved to St. Louis to be with her four brothers.

Madam C. J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in Delta, LA in 1867. Her parents were sharecroppers on a plantation near the Mississippi River. She lost both her parents before she turned 8 years old and went to work in the cotton fields to survive. At 14 she married Moses McWilliams and had a child, Lelia, in 1885. Moses McWilliams died in 1887 and in 1894 she married John Davis. That marriage ended in 1903 and Sarah moved to St. Louis to be with her four brothers.

Sarah’s foray into the hair care industry came out of necessity - she was losing her hair. She experimented with homemade remedies and developed her own recipes. She began selling the products door-to-door and began instructing women on hair and scalp treatments.

A tight hair product market in St. Louis prompted her move in 1906 to Denver. In Denver she married Charles Joseph Walker and became “Madam” C. J. Walker. Though the marriage only lasted six years, it was the name she and her company would be known by from then on.

- This person made history in 1996 as the first African American Frederick P. Rose Director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History

Neil deGrasse Tyson, (1958 - present), was in New York City and discovered his love for the stars at an early age. When he was nine, he took a trip to the Hayden Planetarium at the Museum of Natural History where he got his first taste of star-gazing. Tyson later took classes at the Planetarium and got his own telescope. As a teenager, he would watch the skies from the roof of his apartment building.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, (1958 - present), was in New York City and discovered his love for the stars at an early age. When he was nine, he took a trip to the Hayden Planetarium at the Museum of Natural History where he got his first taste of star-gazing. Tyson later took classes at the Planetarium and got his own telescope. As a teenager, he would watch the skies from the roof of his apartment building.

Tyson received a bachelor’s degree in physics from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1980 and a master’s degree in astronomy from the University of Texas at Austin in 1983. Tyson then earned a master’s (1989) and a doctorate in astrophysics (1991) from Columbia University, New York City.

Soon after graduating from Columbia he landed his dream job… a position at the very Hayden Planetarium where his dreams had started. He started out as a staff scientist. It was only one year before he was named Acting Director of the planetarium. The, only one more year until his was formally named the director of the Planetarium. Tyson is the fifth head of the world-renowned Hayden Planetarium in New York City and the first occupant of its Frederick P. Rose Directorship. He is also a research associate of the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History.

From 1995 to 2005 he wrote monthly essays for Natural History magazine, some of which were collected in Death by Black Hole: And Other Cosmic Quandaries (2007), and in 2000 he wrote an autobiography, The Sky Is Not the Limit: Adventures of an Urban Astrophysicist. His later books included Astrophysics for People in a Hurry (2017) and Letters from an Astrophysicist (2019).

Neil deGrasse Tyson lives in New York City with his wife, a former IT Manager with Bloomberg Financial Markets, and their two kids.

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/tyson-neil-de-grasse-1958/

- This social worker and civil rights and women's activist was the sole female member on the Council of United Civil Rights Leadership, which included other civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Whitney M. Young, and John Lewis.

Dorothy Irene Height (1912 - 2010) was born in Richmond, Virginia to James Edward Height and Fannie Burroughs Height. She earned a college scholarship and was admitted to Barnard College. But the acceptance was rescinded when school realized that she was African American. She then enrolled at New York University instead; her B.S. degree was awarded in 1933, and she earned an M.A. in educational psychology in 1935.

Dorothy Irene Height (1912 - 2010) was born in Richmond, Virginia to James Edward Height and Fannie Burroughs Height. She earned a college scholarship and was admitted to Barnard College. But the acceptance was rescinded when school realized that she was African American. She then enrolled at New York University instead; her B.S. degree was awarded in 1933, and she earned an M.A. in educational psychology in 1935.

In 1937 she accepted a position with the West 137th Street Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA), the branch for African Americans in Harlem. In 1957 she was elected president of the National Council for Negro Women (NCNW), a position she held for the next forty years. In that capacity she aided in efforts to address problems facing people of color both at home and abroad, advocating both legal change and self-help. Height played an important, if often overlooked, role in the emerging civil rights movement.

In the early 1960s she was the sole female member on the Council of United Civil Rights Leadership, an effort to facilitate cooperation among various organizations. Along with the "Big Six" (Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, Whitney M. Young, James Farmer, A. Philip Randolph, and John Lewis), Height helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Height was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004, the county's highest civilian awards. She died in Washington, D.C. In observing her passing, President Barack Obama referred to Dorothy Height as "the godmother of the Civil Rights movement," an encomium that neatly encapsulates the importance of her faith, her role in the civil rights movement, and her identity as a woman.

http://www.biography.com/people/dorothy-height-40743

- What event sparked the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on this day (February 12) in 1909?

The NAACP was formed partly in response to the continuing horrific practice of lynching and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, the capital of Illinois and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln. Appalled at the violence that was committed against blacks, a group of white liberals that included Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard, both the descendants of abolitionists, William English Walling and Dr. Henry Moscowitz issued a call for a meeting to discuss racial justice. Some 60 people, seven of whom were African American (including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell), signed the call, which was released on the centennial of Lincoln's birth.

The NAACP was formed partly in response to the continuing horrific practice of lynching and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, the capital of Illinois and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln. Appalled at the violence that was committed against blacks, a group of white liberals that included Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard, both the descendants of abolitionists, William English Walling and Dr. Henry Moscowitz issued a call for a meeting to discuss racial justice. Some 60 people, seven of whom were African American (including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell), signed the call, which was released on the centennial of Lincoln's birth.

http://www.naacp.org/pages/naacp-history

- This activist who became the first black president of his country was released from prison on this day (February 11) 1990.

Nelson Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in South Africa. Becoming actively involved in the anti-apartheid movement in his 20s, Mandela joined the African National Congress in 1942. In 1963, Mandela was arrested with many fellow leaders of the ANC and brought to stand trial for plotting to overthrow the government by violence. On June 12, 1964, eight of the accused, including Mandela, were sentenced to life imprisonment. During his years in prison, Nelson Mandela was widely accepted as the most significant black leader in South Africa and became a potent symbol of resistance as the anti-apartheid movement gathered strength. Mandela was released on February 11, 1990. After his release, he plunged himself wholeheartedly into his life's work, striving to attain the goals he and others had set out almost four decades earlier. In 1993, Mandela and South African President F.W. de Klerk were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to dismantle the country's apartheid system. In 1994, Mandela was inaugurated as South Africa's first black president. Mandela died at his home in Johannesburg on December 5, 2013, at age 95.

Nelson Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in South Africa. Becoming actively involved in the anti-apartheid movement in his 20s, Mandela joined the African National Congress in 1942. In 1963, Mandela was arrested with many fellow leaders of the ANC and brought to stand trial for plotting to overthrow the government by violence. On June 12, 1964, eight of the accused, including Mandela, were sentenced to life imprisonment. During his years in prison, Nelson Mandela was widely accepted as the most significant black leader in South Africa and became a potent symbol of resistance as the anti-apartheid movement gathered strength. Mandela was released on February 11, 1990. After his release, he plunged himself wholeheartedly into his life's work, striving to attain the goals he and others had set out almost four decades earlier. In 1993, Mandela and South African President F.W. de Klerk were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to dismantle the country's apartheid system. In 1994, Mandela was inaugurated as South Africa's first black president. Mandela died at his home in Johannesburg on December 5, 2013, at age 95.

http://www.history.com/topics/nelson-mandela

- Dudley Randall, dubbed by Black Enterprise magazine in 1978 as "The father of the black poetry movement", originally created this publishing company to publish his own poetry.

Dudley Randall, (1914 - 2000), created the Broadside Press in 1965 in Detroit, Michigan. The press was run out of his home, with limited funds, but managed to publish the major African-American poetry of the time. Randall founded Broadside Press to publish his own poetry but soon expanded to include other poets with focus on producing inexpensive but quality broadsides and books. Randall's first self-published work, a poem titled "The Ballad of Birmingham," was based on the bombing of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Birmingham church 1963, which killed four girls. The majority of Randall's works were based on significant historical events and people that impacted the life of African American people. What made the Broadside Press significant was that it gave African American poets and writers the opportunity to have their works published during a time when major publishing houses did not take these works seriously. The works of Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks and many others that were mainly Detroit natives had their works published by Randall's Broadside Press.

Dudley Randall, (1914 - 2000), created the Broadside Press in 1965 in Detroit, Michigan. The press was run out of his home, with limited funds, but managed to publish the major African-American poetry of the time. Randall founded Broadside Press to publish his own poetry but soon expanded to include other poets with focus on producing inexpensive but quality broadsides and books. Randall's first self-published work, a poem titled "The Ballad of Birmingham," was based on the bombing of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Birmingham church 1963, which killed four girls. The majority of Randall's works were based on significant historical events and people that impacted the life of African American people. What made the Broadside Press significant was that it gave African American poets and writers the opportunity to have their works published during a time when major publishing houses did not take these works seriously. The works of Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks and many others that were mainly Detroit natives had their works published by Randall's Broadside Press.

http://www.broadsidelotuspress.com/dudley_randall_and_broadside.htm

- What is the name of the first black-owned brewery in the US?

Peoples Brewing Company was one of the first black-owned breweries in the nation and the first black-owned brewery in Wisconsin, a state with a storied brewing tradition.

In fall 1970, Theodore “Ted” Mack put together a coalition of Black business owners and bought the Peoples Brewing Company in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Mack used his own savings, as well as funds from the federal government’s Small Business Administration.

Mack’s desire to own a brewery stemmed from his commitment to social activism. He believed that the Black community should become producers of the goods and services that it consumed.

One of the many obstacles Mack encountered was the perception that beer was considered part of white culture. White-owned taverns refused to sell Peoples Beer and many, including those in the Black community, refused to drink it. Mack was surprised and disappointed that the Black community never really supported Peoples in the ways that he expected. He was also frustrated by the SBA’s practice of providing loans to Black businesses but not the support and technical expertise needed to make new businesses successful. Peoples closed in 1972. It had been a Black-owned brewery for just over two years.

While Peoples Brewing is most often cited as the first Black-owned brewery in the nation, some people suggest that two other breweries deserve that distinction: Colony House Brewing Company in Trenton, New Jersey, and Sunshine Brewing Company in Reading, Pennsylvania.

Today, other Black-owned breweries are following in his Mack’s footsteps. Oak Park Brewing Company in Sacramento, California is picking up where Mack left off, selling Peoples Beer, made with the original recipe.

- What year was Martin Luther King Day first observed as a federal holiday?

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born in Atlanta in 1929, the son of a Baptist minister. He received a doctorate degree in theology and in 1955 organized the first major protest of the civil rights movement: the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott. In 1963, he led his massive March on Washington, in which he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” address.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born in Atlanta in 1929, the son of a Baptist minister. He received a doctorate degree in theology and in 1955 organized the first major protest of the civil rights movement: the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott. In 1963, he led his massive March on Washington, in which he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” address.

King was the first modern private citizen to be honored with a federal holiday. The fight to make the Martin Luther King Jr. birthday a holiday took 32 years, a lot of campaigning, and guest appearances including Stevie Wonder, Ted Kennedy, and the National Football League.

King’s birthday was finally approved as a federal holiday in 1983. The first federal holiday was celebrated in 1986 but it took years for observance to filter through to every state. Several Southern states promptly combined Martin Luther, King, Jr. Day with holidays that uplifted Confederate leader Robert E. Lee, who was born on January 19.

Arizona initially observed the holiday, then rescinded it, leading to a years-long scuffle over whether to celebrate King that ended in multiple public referenda, major boycotts of the state, and a final voter registration push that helped propel a final referendum toward success in 1992. It wasn’t until 2000 that every state in the Union finally observed Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Martin-Luther-King-Jr-Day

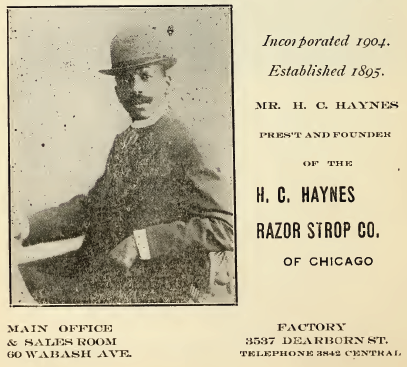

- What’s the name of the African American that invented the “razor strop” making the lives of barbers easier?

C. Haynes, born of slave parents in Selma, Alabama, worked as a barber's apprentice which gave him the idea for a "ready to use razor strop". Barbers were using parts at harnesses as "razor strops", which proved difficult and not always effective. Haynes first produced his 'strop" in his home and sold them to barbers. He later was able to increase production, advertise, and develop mail orders in which he supplied razors and scissors. By 1899, with the aid at his wife, the "Haynes strop" was a trade fixture. He obtained a patent, and was able to introduce and make a connection with a German manufacturer. By 1904, Haynes had imported an estimated 6,000 razor strops.

C. Haynes, born of slave parents in Selma, Alabama, worked as a barber's apprentice which gave him the idea for a "ready to use razor strop". Barbers were using parts at harnesses as "razor strops", which proved difficult and not always effective. Haynes first produced his 'strop" in his home and sold them to barbers. He later was able to increase production, advertise, and develop mail orders in which he supplied razors and scissors. By 1899, with the aid at his wife, the "Haynes strop" was a trade fixture. He obtained a patent, and was able to introduce and make a connection with a German manufacturer. By 1904, Haynes had imported an estimated 6,000 razor strops.

http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2932

- This prolific inventor holds 5 patents, the most of any African American woman in history.

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner (May 17, 1912 – January 13, 2006) was an African-American inventor most noted for her development of the sanitary belt, the precursor to self-adhesive maxi pads.

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner (May 17, 1912 – January 13, 2006) was an African-American inventor most noted for her development of the sanitary belt, the precursor to self-adhesive maxi pads.

She was born in Monroe, North Carolina and credited her innovative mindset to her family full of inventors. Her father Sidney Nathaniel Davidson invented a pants presser, which was later patented in 1914. Her sister, Mildred Davidson, broke into the board game industry creating “Family Treedition.” While her paternal grandfather, Robert Phromeberger invented the tricolor light signal for trains.

From childhood to becoming an early adult, Kenner was consistently creating things. In 1931 she enrolled at Howard University to cultivate her creative mindset. Soon after, she was unable to afford tuition and ended up dropping out. She took on odd jobs such as babysitting before landing a position as a federal employee, but she continued tinkering in her spare time.

Between 1956 and 1987 she received five patents for her household and personal item creations. Her patents included: a carrier attachment for an invalid walker (1959), a bathroom tissue holder (1982), and a back washer mounted on a shower wall and bathtub (1987). But perhaps she is most famous for inventing a sanitary belt in the 1920’s but was not patented until 1956.

Kenner invented both the sanitary belt and the sanitary belt with moisture-proof napkin pocket. The sanitary belt gave women a better alternative for handling their periods. It was patented 30 years after she invented it, because the company who was initially interested in her creation rejected it when they learned that Kenner was African American.

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/mb5yap/mary-beatrice-davidson-kenner-sanitary-belt

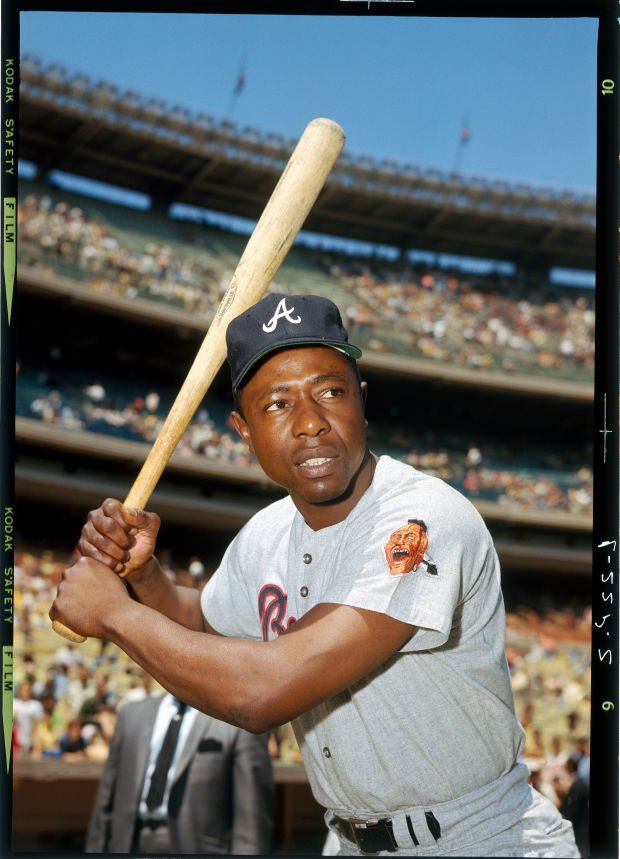

- This baseball great, who ascended the ranks of the Negro Leagues to become a Major League Baseball icon, was born on this day (February 5) in 1934?

Henry Louis Aaron was born February 5, 1934, in Mobile, Alabama. He began his professional baseball career in 1952 in the Negro League and joined the Milwaukee Braves of the major league in 1954, eight years after Jackie Robinson had integrated baseball. Aaron spent most of his 23 MLB seasons as an outfielder for the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves, during which time he set many records. On April 8, 1974, he conquered Babe Ruth and one of the most hallowed records in sports by knocking his 715th home run. He ended his career with a .305 batting average, 755 home runs, 3,771 hits, 2,297 RBI, three Gold Gloves, a World Series championship and an MVP award. Aaron's home run record has since been broken by Barry Bonds, but he remains one of just three members of the 700-home run club.

Henry Louis Aaron was born February 5, 1934, in Mobile, Alabama. He began his professional baseball career in 1952 in the Negro League and joined the Milwaukee Braves of the major league in 1954, eight years after Jackie Robinson had integrated baseball. Aaron spent most of his 23 MLB seasons as an outfielder for the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves, during which time he set many records. On April 8, 1974, he conquered Babe Ruth and one of the most hallowed records in sports by knocking his 715th home run. He ended his career with a .305 batting average, 755 home runs, 3,771 hits, 2,297 RBI, three Gold Gloves, a World Series championship and an MVP award. Aaron's home run record has since been broken by Barry Bonds, but he remains one of just three members of the 700-home run club.

http://baseballhall.org/hof/aaron-hank

- This civil rights activist, born on this day (February 4) in 1913, was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999.

Civil rights activist Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama. In December of 1955, Mrs. Parks was arrested and fined for refusing to surrender her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. This brave act of defiance spurred a city-wide boycott and began a movement that ended legal segregation in America. Rosa Parks received many accolades during her lifetime, including the NAACP's highest award.

Civil rights activist Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama. In December of 1955, Mrs. Parks was arrested and fined for refusing to surrender her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. This brave act of defiance spurred a city-wide boycott and began a movement that ended legal segregation in America. Rosa Parks received many accolades during her lifetime, including the NAACP's highest award.

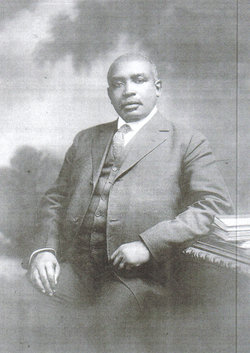

- What African American organized Keystone Bank in 1922?

John Cornelius Asbury (1862-1941) was an outstanding businessman and politician. He was born in Pennsylvania and was educated at Washington and Jefferson College and received a law degree from Howard University. He practiced law in Virginia where he held several political offices, among them assistant state’s attorney in Norfolk. In 1902 he organized the Keystone Aide Society and opened the Eden Cemetery in Philadelphia, making burial plots available to African Americans. Its stockholders earned dividends each year during its operations. He organized the Keystone Bank in 1922, which was forced to close during the depression years of the thirties; however, not a single depositor lost money.

John Cornelius Asbury (1862-1941) was an outstanding businessman and politician. He was born in Pennsylvania and was educated at Washington and Jefferson College and received a law degree from Howard University. He practiced law in Virginia where he held several political offices, among them assistant state’s attorney in Norfolk. In 1902 he organized the Keystone Aide Society and opened the Eden Cemetery in Philadelphia, making burial plots available to African Americans. Its stockholders earned dividends each year during its operations. He organized the Keystone Bank in 1922, which was forced to close during the depression years of the thirties; however, not a single depositor lost money.

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=124218356

- This civil rights effort is believed to be the first sit-in to protest segregation in America.

Five men were arrested at the Alexandria Library on Queen Street on Aug. 21, 1939, because they defied the exclusion of black people. (Courtesy Alexandria Black History Museum)

The Alexandria Library sit-in was among the first of what would become a key tool in the fight for civil rights. It was held on August 21, 1939 and was orchestrated by an African American lawyer named Samuel Wilbert Tucker, born in Alexandria to educated, middle-class parents in 1913. He attended Howard University for undergrad and studied law in his own time at the Library of Congress. With a personal understanding of the importance of libraries, Tucker resolved to extend the Alexandria public library access to the black community.

The library was public, and there was no law prohibiting anyone from using it regardless of race. But the library was still treated as a segregated building, and African Americans were not given cards to the library. Tucker organized the sit-in with six others — five who entered the library, knowing the service would be denied to them and a sixth to act as a lookout and alert the press when the others were threatened with arrest.

Otto Tucker, William “Buddy” Evans, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray and Clarence “Buck” Strange entered the library and requested library cards, knowing they would be refused. After they were told they couldn’t use the library, the men picked up books from the shelves and began reading quietly. When police arrived, Evans asked what would happen if they still didn’t leave, to which the officer said they would be arrested.

The five were charged with “disorderly conduct,” as no crime had actually been committed. Samuel Tucker acted as their representation in a court case however, the judge avoided issuing a ruling, resulting in the five never being declared guilty or not guilty, but also not being forced to serve time or pay a fine.

The City of Alexandria fast-tracked the development of a Black-only library — the Robert Robinson Library. Tucker went on to work for the NAACP and argue more than 50 cases in Virginia’s Massive Resistance following Brown v. Board, appearing before the Supreme Court several times. The Alexandria library system was finally integrated to black adults in 1959 and the Robert Robinson library closed in 1962 when black children were also allowed in the city libraries.

The charges against the five men were not officially dismissed by the city until October 2019.

- This activist, author and academic scholar was a candidate for Vice President on the Communist Party USA ticket in 1980.

Angela Davis was born on January 26, 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama. Her father, Frank Davis, was a service station owner and her mother, Sallye Davis, was an elementary school teacher. In 1961 Davis enrolled in Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, earning her B.A. (magna cum laude) in 1965. In 1967 Davis joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and then the Black Panther Party. She also continued her education, earning an M.A. from the University of California at San Diego in 1968. Davis moved further to the left in the same year when she became a member of the American Communist Party.

Angela Davis was born on January 26, 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama. Her father, Frank Davis, was a service station owner and her mother, Sallye Davis, was an elementary school teacher. In 1961 Davis enrolled in Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, earning her B.A. (magna cum laude) in 1965. In 1967 Davis joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and then the Black Panther Party. She also continued her education, earning an M.A. from the University of California at San Diego in 1968. Davis moved further to the left in the same year when she became a member of the American Communist Party.

In 1970, Davis became a suspect in a failed attempt to free prisoners who were on trial that resulted in death of Superior Court Judge Harold Haley and three others including the assailant. She fled to avoid arrest and was placed on the FBI’s most wanted list and was eventually captured. During her high profile trial in 1972, Davis was acquitted on all charges. The incident generated an outcry against Davis and then California Governor Ronald Reagan campaigned to prevent her from teaching in the California State university system. Despite the governor’s objection, Davis became a lecturer in women’s and ethnic studies at San Francisco State University in 1977.

As a scholar, Davis has authored five books, including Angela Davis: An Autobiography in 1974; Women, Race, and Class in 1983; and Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday in 1999. In the political arena, Davis ran unsuccessfully in 1980 and 1984 on the Communist Party ticket for vice president of the United States. Davis continues to be an activist and lecturer as Professor Emeritus of History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies at the University of California at Santa Cruz. She is also a Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Women's and Gender Studies Department at Syracuse University.